What is a synagogue?

by Till Grallert

|

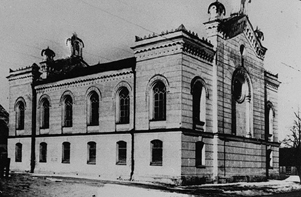

Introduction For this symposium on the future usage and preservation of the Synagogue-building in Kuldiga I would like to focus on the different functions of Synagogue within the framework of urban Jewish communities in the past rather than on the building itself. I think that by reviving certain functions once attached to a specific place within the urban space we can preserve the memory of the deceased, who had formed a living community. Gathering together, assembling with one another, the creation of communal ties beyond mere kinship seem to be the most basic necessities of human life. Being of equal importance to the physical supplies of food, water and air. Hence the social institution of gathering within a framework of multidimensional aspects is to be found in mankind’s history from the mists of ancient ages up to our times. The synagogue is one of the infinite number of its possible realisations. It is a social institution for the gathering of people whose distinctive bond is their Jewishness. It is a physical shell for the liturgical requirements, which themselves are the very constitutive elements for the community. It is a shell, which provides the physical environment for experiencing the bonds of community. Facilitated by the announcement and celebration of the most important events in ones individual and social life. The birth of a new child, its admission to the community, its coming of age, its marriage, its death. Taking the scholarly debate on the origins of synagogé and proseuché in antiquity as a starting point I am going to elaborate the question „What is a Synagogue?“ and the different concepts of communal organization connected to possible answers. As an analytical framework I suggest that we split our view on a phenomenon called synagogue into four aspects. By doing so following Anders Runessons methodology. The four aspects are as follows not implying any hierarchical structure by their place of occurrence in the listing (Runesson 2001, S.34f.): 1. Synagogue as an institution: this comprises aspects of formal secular and religious authority closely linked to a well-established and institutionalized community. 2. Synagogue as liturgy: all aspects which might be considered as „religious“ 3. Synagogue as non-liturgical activities: all activities which might not be classified as purely religious, such as gathering for a chat, educational activities, judicial activities, guesthouse, charity, archive etc. 4. Synagogue as a building All those aspects find there expression in the Jewish terminology used in Eastern Europe for places and institutions which we today might call Synagogue: bet knesset (hebr. „house of assembly“), bet ha-midrash (hebr. „house of exegesis“), bet ha-tfila (hebr. „house of prayer“), shul (yid. „school“), shtible and kloiz (yid. „small chamber“). As every term is focusing on a different aspect of communal life and only one, bet ha-tfila, is referring explicitly to religious functions we may assume that a representative religious building is not one of the fundamental necessities of Jewish life. I don’t want to present today a comprehensive socio-historical study of the synagogue nor do I attempt to construct in front of you the coherent image of the synagogue. I rather want to bring your attention to some facets of the phenomenon synagogue once probably significant at this place. What is a Synagogue? Any answer on the question „What is a Synagogue?“ is heavily dependent on a set of presumptions about its nature or in other words: it is dependent on what we are looking for. Our first necessary presumption is the existence of something with distinctive characteristics, something that we would call „Synagogue“; something that we can clearly distinguish from any non-Synagogue. We presume an institution sheltered by specific architectural features, whose most basic and constitutive elements weren’t subject to substantial change in its contexts of space and time. We are looking for a set of functions that are clearly identifiable as specific Jewish functions, which enable us to trace a history of the „Synagogue“. So far it seems to be an ontological quest for the very substance of Synagogue and I have to commit that I don’t see a way around this essentialist trap as far as we want to trace the history of anything through the times. But at any time, we should be conscious about the constructed nature of all our assumptions. Every single one of them is coined by our individual and collective experience and memory of Synagogue (in modern times). Any set of criteria - even though they might be quite reasonably chosen - is reminiscent of our contemporary construction of Synagogue and tracing this set back through the times will lead us to find structures, which we today would label with the term Synagogue. But we can’t be sure about the conceptions their contemporaries had about them. In other words: we can't know whether such structures were in fact synagogues. Origin of the Synagogue and the sources Actually many scholars who worked on the origins of the synagogue ran into that very trap. By projecting later conceptions onto findings from earlier times, they presented structures from Israel and the Diaspora as synagogues. Using these physical structures then as proof for the correctness of the later scriptures. The only surviving narration of the liturgical developments of Judaism after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE is the rabbinical narration. The narration of a former minority within Judaism to the normative base of Judaism during the 500 years anteceding the Temple’s destruction. A narration that inter alia was meant to present religious credentials for emerging institutions by dating them back into an unchallenged past. For this talk, I would like to take the very term synagogue as a starting point. Being of Greek origin synagogé denotes an “assembly” or “gathering” of any kind in general. During Hellenistic times it was a common term for the designation of “community” and “congregation” both in secular and religious contexts, but not particular Jewish ones. In the LXX, the Greek translation of the Tanakh from the 3./2. centuries BCE, synagogé in its meaning of “gathering” is used as translation for a variety of Hebrew terms such as kahal or edah. Beginning with the first centuries CE synagogé was increasingly used for the designation of the building sheltering the “community” as well as the „community“ itself. By that replacing the earlier proseuché, „place of prayer“ used in sources form Hellenistic times, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, to designate Jewish places of worship other than the Temple. Having that said one of the two most common Hebrew terms coined by the later rabbinical Sources (of mishna and talmud) to designate a synagogue is strikingly similar to the Greek synagogé: bet knesset meaning „house of assembly“. The other one is bet ha-midrash, house of study or interpretation (of the Torah) focuses on a specific purpose for gathering together. The scholarly debate concerning those to institutions and their assumed existence in antiquity centres on the question whether the terms applied originally to the same building, which was denoted depending on its function (as shelter for the assembly or for the study and interpretation of the holy scriptures,) or whether they applied to two distinct kinds of buildings. The archaeological findings from the land of Israel and the Diaspora of ancient times can’t help us here, for there interpretation depends on the conceptualization of Synagogue and not vice versa. Actually the question on the distinctive spatial structures which are characteristic for the bet ha-midrash, the learning institution, remains unsolved - which might be the reason for the almost entire absence of identified batei ha-midrash. However, my main concern is the fact that all those terms highlight institutional and spatial aspects respectively but not liturgical characteristics. So far, we have philologically established that a synagogue is an assembly as well as its protective shell. Considering our made assumption on the existence of distinctive features we have to commit that this is not sufficient for a conceptualization of synagogue. Any given synagogue might an assembly but not any assembly is necessarily a synagogue. The question is which aspect makes a specific assembly into a synagogue? The most basic quality to distinguish between a synagogue and other institutions and structures then is its Jewishness. Even if the synagogue is absolutely similar in any other aspect to other structures, its Jewishness remains to be the decisive feature. In order to be of interest to us a synagogue has to be a Jewish institution. Having in mind the above made distinction between liturgical, spatial, non-liturgical and institutional aspects our first point of interest is the liturgical aspect of synagogue, as the aspect, which makes the assembly into a synagogue. After establishing the liturgical aspects as distinctive features, we should ask for the spatial aspect of this activities. Where did and where do the liturgical activities take place? Do they necessitate a special spatial setting in order to be conducted? After we have possibly identified a certain physical characteristics of synagogue we should go even further by asking what if at all were other non-liturgical activities carried out at the same space or in its close proximity? At last, we have to address the question whether all those aspects were encompassed and provided by an institutional framework. The liturgical aspects So let us turn to the synagogue liturgy. This liturgy comprises today three main elements in various arrangements: first, recitations from the Torah and the Prophets, as well as Psalms. Second, prayers like the shma’ and the ’amida. Third, a sermon or interpretative commentary on the foregone recitation. We will begin our elaboration of the liturgical aspects with the recitation, for that clearly requires an auditorium, an assembly, as we will see. qriyat torah and bet knesset The main function of the synagogue as assembly and that with the longest traceable history is the public recitation of the Torah. That is the loud declamation of the Torah in front of an auditorium of a minimum of ten men rather than the reading and studying of the Holy Scriptures for oneself. Even though the common Hebrew terms for such an institution, bet knesset and bet ha-midrash, don’t appear in the written Torah the rabbinical narration honours Moses with the foundation of the institution of synagogue, which is identified with the invocation for Torah recitation in Deuteronomy 31:10-13: 10 And Moses commanded them, saying, At the end of every seven years, in the solemnity of the year of release, in the feast of tabernacles, 11 When all Israel is come to appear before the Lord thy God in the place which he shall choose, thou shalt read this law before all Israel in their hearing. 12 Gather the people together, men, and women, and children, and thy stranger that is within thy gates, that they may hear, and that they may learn, and fear the Lord your God, and observe to do all the words of this law: 13 And that their children, which have not known any thing, may hear, and learn to fear the Lord your God, as long as ye live in the land whither ye go over Jordan to possess it. (This is by far not the only passage on public recitation; vgl. Runesson 2001, S.240ff.) Independently from any institutionalized form of synagogue, we learn from this passage that the reading has to be carried out in public and for the purpose of teaching the sacred laws to all of Israel. A momentum, which will gain importance in later rabbinical teachings on the Synagogue as, bet ha-midrash, an institution I will refer to later. The first reliable historical sources that mention this function of the synagogue by the terms synagogé and proseuché are Josephus and Philo - both describing the recitations as the main characteristic. The sources of the rabbinical halakha, the Jewish law, devote themselves to the issue of Synagogue in the Tractate Megillah, that is the comment on the Esther Scroll. Here we learn that the Scroll of Esther has to be declaimed publicly to Israel within the framework of a particular location, the bet knesset. Taking this as a starting point the halakhic scriptures further elaborate the functions of Synagogue as place of assembly for the recitation of the Torah in general. As the famous Jacob Neusner has put it in his encyclopaedic work on the Halakha: "And what, within the framework of the halakha, can we possibly mean by 'synagogue'? The answer is, the synagogue represents the occasion at which ten or more Israelite males assemble and so embody Israel, and provides for the declamation of the Torah to Israel: it is Sinai, no where in particular […]"(p.408) "It is that the declamation of Scripture takes places most suitably in the congregation gathered in a particular building erected and set aside for that purpose - not for prayer, not for sacrifice, not for study, but for Torah-declamation. That alone defines within the halakha what the synagogue serves - that alone." (p.432) By that, we establish that the only two things indispensable for the synagogal service are the assembly of ten male believers, the minyan, and the Torah-scrolls. This concept of synagogue as an occasion clearly negates the idea of a holy building like the Temple in Jerusalem. Though a certain kind of shelter and protection for the Torah rolls made from parchment seems to be suitable for practical reasons. This necessity soon evolved into a hierarchical system of protective layers around the scrolls with the synagogue building as the uttermost layer and the one least sacred. That is supported by the above named Tractate Megillah, which states on the question of the disposal of a Synagogue-building, that it is allowed to sell a Synagogue for the acquisition of the torah scrolls, but not the other way around, for the latter is holier. Before we turn to the Torah scrolls and their decisive role in synagogue design I would like to have a look at the grade of institutionalization required for the declamation in its pure sense: no organizational structure would be necessary, as every adult Jewish male is able to fulfil the community’s obligation to hear the Torah read out. By that, a certain kind of equality is established between at least the adult male members of the congregation - a concept, which was completely absent in the Temple, where a hierarchical caste of priests conducted the worships and offerings for all of Israel. However, by reciting the Torah in a certain and linear manner we a disparity between a speaker and the auditorium, even though anybody could, not everybody will indeed become the reader. So we conclude that a kind of hierarchy is introduced by practically excluding somebody from the reading, but not the auditorium. In later times, relevant for the Kuldiga synagogue, the mitzvah of reciting was commonly bound to grants to the institutionalized congregation. tfilah The second liturgical aspect of the synagogue as listed above is the communal prayer. This activity is first introduced by the sources with the Talmud Yerushalmi, that is by the late fourth century CE Nevertheless, nowhere communal prayer is made compulsory for the individual. Prayer is considered, as something taking place between the individual and God and therefore as something that doesn’t require a certain spatial shelter. So we may consider an institutionalized form of communal prayer in the synagogue an important aspect but not distinctive for prayer might be carried out anywhere. I would tend to see communal prayer as a social function that provides a sense of unity and belonging to the community different from the passive unity of an auditorium - a feeling of equality not experienced in the dichotomy of reciting and listening. derasha and bet ha-midrash For as we have seen in the quoted passage from the Deuteronomy learning and teaching the law to Israel are the main function of the Torah recitation, I would like to draw our attention now to the bet ha-midrash, the „house of study and interpretation“. Even though its name indicates a function of essentially non-liturgical character, the rabbinical sources state that the assembly for the declamation of the Torah was sheltered by the bet ha-midrash as well. For a distinction between the otherwise exchangeable terms of bet ha-midrash and bet knesset as Zeev Safrai has pointed out that the latter was used to designate a group of people and not a building at all. Some scholars have pointed out that the term bet ha-midrash as synagogue has to be of rather late origin because of its tautological nature. Midrash itself is already indicating a place for derasha, interpretation, by its grammatical structure of locative. Bet ha-midrash has rather to be understood as deriving from the root darasha „to seek“, „to inquire“ as a place where people sought the religious guidance of the more learned ones. This connotation then evolved into bet ha-midrash as „place of Divine communion“. Historically the institution of derasha, the commentary, the interpretation, the authoritative discussion of the Torah was already an important part of Jewish life before the destruction of the Temple. Because most of the common people didn’t speak Hebrew in daily life for centuries before the destruction, but rather Aramaic and Greek or other languages of the Diaspora. As they became increasingly dependent on learned men for guidance in daily matters, the necessity of educational institutions for those meant to give such guidance became more and more evident. Institutions for the study of the Torah and its means of interpretation. Institutions for the development of a „new“ Judaism centred on the Torah, deprived of its religious focal point, the Temple, and deprived of its political sovereignty. However, the mishnaic sources point out that soon a dual structure evolved. A structure of liturgical institutions which established a hierarchy between the learned men and the common people. We are told that some sages disliked the idea to go the batei ha-knesset of the common people for delivering a derasha but rather preferred to have the Torah recited in the realm of their studying assembly - being probably more interested in the scholarly debate with their colleagues than in the talk to lower strata of society. As far as more than ten men were present at such a place of Torah study it was absolutely sufficient to figure as synagogue - as we have noted above. Hence on the one hand we have the term bet ha-midrash came to designate an institutionalized liturgy comprising the declamation and the exegesis and on the other hand the bet midrash as a distinctive learning institution later developing into the yeshivot. Especially in the latter sense it necessitated some kind of library and a physical shelter for such objects of value. Sometimes the spatial units for the purpose of assembly, bet knesset, and such for the purpose of study, bet ha-midrash, were merged into one compound / complex designated as synagogue. In any case, the exegetic interpretation necessitated a grade of institutionalized authority not known to us yet within the framework of recitation and prayer. The principal chance for everybody to partake in the active in-group was ceased and bound to conditions. The spatial aspects: aron and bima The aforementioned sacred status of the Torah scrolls makes it necessary to have a protective shell for the scrolls, which are made from parchment and some sort of supporting stand for the scroll during the reading itself. The shelter of the scrolls soon took the shape of a shrine mostly attached to a wall, called aron kodesh, holy Ark, while the reading took place from a raised platform with an attached console for the laying down the scrolls, the bima. For Dominique Jarrassé the spatial arrangement of those two main elements of the Synagogue building’s interior figures as indication for communal identities. The classical spatial arrangement observed in Ashkenazi communities, which is not mentioned in normative sources of the rabbinical period is as follows: 1) The aron is placed at the wall facing Jerusalem, which is usually identified with an eastward orientation in Europe and America. 2) The bima is placed in the centre of the building. A practical reason for that position is the audibility of the reader and the congregation's ability to walk around the scrolls though the post Talmudic narrations focus mainly on the symbolical function of the bima - namely as a symbol of the Sinai, where Israel received the Decalogue. Furthermore the bima is often placed slightly off-centre to the west, so that the Scrolls are centred when placed on the console for reading. This central setting of the bima was made a normative regulation as late as the twelfth century CE by Maimonides (d. 1204). A regulation whose binding character was subject to rabbinical discourses during the nineteenth century. However, this central setting of the bima fits the non-hierarchical organizational structure of the assembly outlined above, as every male member of the community would sit in almost the same distance around the centred Torah. Although the seats in close proximity to the aron were the most esteemed ones in the actual buildings and subject to constant litigation as we can learn from the rich responsa literature on that topic. A setting, which we can observe in almost all of the Synagogues of Eastern Europe. The central setting of the bima is to be found in the Kuldiga Synagogue. But in the middle of the nineteenth century, we witness a change in that traditional setting. With the rise of the importance of the sermon, which was not held from the bima, reserved for the recitation alone, but rather in front of the aron the bima became increasingly disturbing for the congregation. For that reason and the increasing acculturation of the Jewish communities in western Europe, which began to denote themselves as citizens of a certain state being of Mosaic believe, some congregations began to move the bima from the centre towards the aron joining them into something resembling the choir of Christian churches. Even though that was mainly the case in reform and conservative congregations, it even became a topic in responsa on the erection and remodelling of orthodox Synagogues. However, while this change provided for more space for the seating arrangement it was also a step towards the separation between the congregation and liturgy, or more particularly between the congregation and the liturgical personal such as the cantor, hazzan, and the rabbi. For the exterior appearance of the building no provision was made by the normative rabbinical sources. So we conclude that the building itself was determined by the additional activities it was meant to shelter and by the socio-political conditions prevailing for a specific community. In times of unrest no one would have dared to erect a synagogue building clearly distinguishable as such from the outside. Synagogue as Institution: the authority of the rabbi Most of the activities mentioned above require some sort of trained personal. Personal who at least devote part of their time to the service of the community. The most outstanding post would be the rabbi. The term „rabbi“ is a little bit confusing here, being introduced as designation for religious authorities by Talmudic times it denotes at least two distinct kinds of authority: a) the rabbi who as a learned and charismatic men gathers a congregation of students around him without being elected by any kind of local community, but probably settling with an existing local community. b) the rabbi, who is elected religious authority of a organized congregation. In any case, he is the normative authority: delivering the derasha during the services, deciding every case concerning Jewish law and by that being involved into every aspect of individual and communal life. However important these functions are, the office of a professional rabbinate is a rather young development. In Europe, the office of professional rabbi, getting paid by an organized congregation isn’t known to us before the thirteenth century. Reasons for that might be, as others have argued, the relatively unstable conditions prevailing for Jewish communities within the Christian societies. A community has to have a certain minimum number of members able to provide funds. That in turn requires a relative stable political, social and economic surrounding, where Jews were at least granted permanent settlement, religious practice and exertion of economic activities. With the course of the nineteenth century and Reform Judaism such functions as leading in prayer, blessing of the people, the performance of marriages and so forth became part of the conception of the rabbinate, while others, mainly judicial ones ceased to do so. The conception of rabbi changed towards a clerically priesthood and correspondingly the synagogue was named „Temple“. The most important branch of Judaism in Eastern Europe from the eighteenth century onward, the Hassidim, did away with all officially appointed staff. Here again a member of the congregation led the services. Their Yiddish terminology of shtibl and kloyz, of „small room“ and „secluded room“ rather than a „house of the assembly“ leaves the field open to discussion whether we should call them synagogues as well. Concluding remarks Let me summarize our thoughts on the phenomenon synagogue made today. Synagogue is basically an Jewish assembly facilitated by the religious necessity of Torah recitation, sheltered by a physical structure that could but not necessary does provide for more non-liturgical activities. A physical structure, which bestows the individual with the essential experience of belonging to a social unit. For an institutionalized conjunction of many (if not all) of the above listed functions and aspects in a single and representative building we certainly need to have an organized and officially recognized community with the capability of providing certain funds for the building itself, its maintenance and the associated personal of at least a Rabbi. And by that we can assume an organizational framework with a certain hierarchical structure, which is clearly beyond the religiously required assembly of ten men for the Torah declamation. |