Jewish life in Kuldiga in the 1920s

by Bramie Lenhoff

|

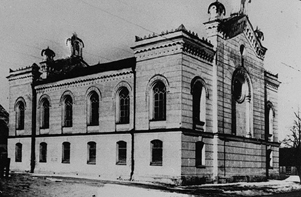

1. Why am I here? All of my known ancestors came from Kurland (Kurzeme) within 160 km of Kuldiga, and many came from Kuldiga itself. My mother, her parents and both her grandfathers were from Kuldiga, and this extended back to earlier generations as well. My father's family was more widely distributed, but his mother was born in Sabile nearby, and her sister was born in Kuldiga too. However, my I was born in South Africa, so why the interest? 2. Many of my parents' relatives and friends when I was growing up were also emigrants from eastern Europe generally and from Kurland in particular, including from Kuldiga. Even many decades after leaving what was by no means an easy life here, these people would use the Yiddish expression "in der Heim" (at home) to describe their places of origin. In our home my mother would talk fondly of Goldingen. She passed away a few years ago, but I will try to convey a little of what I understand of her childhood here and to use this as a basis to discuss more broadly the lives of the Jewish residents of Kuldiga in the early 20th century. For a more authentic representation, I encourage you to speak to someone I am especially pleased has joined us this week, namely my uncle, Dr. Elliott Lanford, who was born in Kuldiga in 1910 and has returned for the first time since his family emigrated in 1928. 3. I can not provide as detailed and well-informed a historical picture of Jewish life in Kuldiga or in Kurland or Latvia generally as some of the professional historians from whom you have heard or will hear. However, it is interesting to start with some statistics based on the 1881 census in Kurland, which shows the distribution of occupations of the different ethnic groups in the towns of Kurland. For the Jewish population, the most common occupations were traders and shopkeepers, women working as messengers, and various kinds of craftsmen, especially tailors and shoemakers. Only about 200 people are listed as being occupied with intellectual work. These statistics omit the more rural population, and so do not capture the Jewish contribution to agriculture, for example. 4. Kuldiga around the turn of the century had a large Jewish population. According to the 1897 census, the total population was 9,720, and depending on which source one uses, the Jewish population was either 2,543 (26%) or 1,368 (14%) -- either way a significant fraction. The Jewish population of the towns of Kurland was decreasing during this period, partly to families moving to the larger cities such as Liepaja and Ventspils and partly due to emigration, especially following the abortive rising of 1905, to which there is a monument just a few hundred metres from here. However, around the time of World War I there was certainly still a significant Jewish population. 5. The early part of World War I was a catastrophic time for Jewish life in Kurland. In the book "The Jews of Latvia", our cousin Shaul Lipschitz wrote that after German progress against the Russian army in 1915, "The Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, Nikolai Nikolaevitch, an uncle of the Czar, Nikolai II, decreed on April 28, 1915 that the entire Jewish population of Kurland should be expelled within twenty-four hours. The confusion, anxiety and panic of the Jews on that memorable day of April 28, 1915 can hardly be described. Jewish leaders appealed to the authorities, but all they could achieve was a postponement of several days. Five provinces (Guberni) in the heart of Russia were designated for the resettlement of the expelled Jews; namely Mogiliov, Chernigov, Poltava, Voronezh and Yekaterinoslav." The Lipschitz family, thanks to their educated children's consulting an atlas, went to Orsha in Mogiliov gubernia because it was relatively close by; much of the Jewish population of Ventspils followed the same route. My family, on the other hand, ended up very far away, in Orechov in Yekaterinoslav gubernia in what is now Ukraine. The train travel was in cattle cars under terrible conditions, and very few possessions could be taken along. 6. The effect of the expulsion was dramatic. By 1920 the total population of Kuldiga was down to 4,924, with only 783 Jews, and it is estimated that 40,000 people were expelled from Kurland overall, and only 16,000-17,000 returned to their earlier home areas. My mother's family, including my uncle here, endured a horrific period including the death of their mother, famine and pogroms, and returned to Kuldiga, now part of independent Latvia, in 1922. Some of their travel documents are shown here. 7. The family settled back into life in Kuldiga, now in the town, where they lived on Kalnu iela. My grandfather was a butcher selling meat in the market place (Tirgus laukums). Their life as part of the Jewish community serves as a guide to the life of that community. 8. Immediately in 1922 the children, who did not attend school for significant periods during their exile, were now back at school. Here is Eli as part of a school group in 1922, and my mother in a scene with a characteristic Kuldiga background in 1923. 9. The family was also, of course, part of Jewish life in Kuldiga. Eli celebrated his Bar-Mitzvah in 1923, and this of course raises the subject that we are all here to consider, namely the synagogue. The Yiddish word for synagogue is shul, which has its roots in the German word Schule, or school. Thus the synagogue was not just a place of worship but also a place of learning, and over the centuries synagogues had been the site of learning and scholarship, which were highly prized by Jewish communities. While the learning originally focused, of course, on religious learning, secular education had an important role too, and although I do not have historical evidence for this, I imagine that this became increasingly important in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. 10. This postcard, for instance, was sent by my grandmother, who had worked as a governess in Odessa; it is addressed in Russian but written in German in the formal Fraktur script. When my mother attended school in Kuldiga in the 1920s, she studied five languages: Latvian, Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian and German. My uncle was fortunate to be able to attend a Gymnasium in Ventspils, where he stayed with an aunt. 11. My mother's autograph book includes entries written by her friends and teachers in multiple languages -- Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, German. We do not know how many of these people survived the Holocaust. For example, this page was written by Moshe Sadowitsch, who was listed in the census as being a worker still living in Kuldiga at the start of the war, but his fate is not known. 12. There was evidently an active communal life. These are pictures taken at the Lag Ba'Omer picnic -- a minor Jewish holiday -- in 1925. Included are my mother's and my uncle's school classes, with the same teachers present in both. 13. I do not know where the actual school building was. The building on Smilsu iela, just behind the synagogue, which is now the music school, was apparently built in 1928, and still has the same outward appearance that it did then. This picture of a classroom was taken around 1930, and may have been from in that building. 14. The socio-economic conditions of the time were mixed. While many families depended on charity, and my mother's family struggled economically, there was at the same time an increasing general prosperity. By 1935, 95 of the 205 businesses in Kuldiga were owned by Jews, including the Vulkans match factory, owned by Hirschmann, whose twin daughters were my mother's friends. My uncle also remembers friends who came from wealthy families. 15. This change is also apparent in the occupations of Jews throughout Latvia. The statistics for Latvia overall in 1935 may not be representative for Kurzeme, where only about 12,000 of the approximately 90,000 increasingly urbanized Jews remained, but they are still informative. Jews were increasingly employed in the professions, the arts and health care, but most were still involved in trade, commerce and industry, albeit now much more extensively as owners of enterprises. Most companies were fairly small, employing just a few people, and they covered a wide range of industries, with clothing and shoes most prominent. Thus within a generation or two they had gone from being tailors and shoemakers to owning companies making clothes and shoes. 16. Being at the less prosperous end of the spectrum, my mother's family emigrated to South Africa in 1928, after the eldest two sons had left earlier to establish themselves. Here are my mother's school friends and teachers at the time. Some of these people may also have emigrated but some -- perhaps the most successful families -- stayed, and we do not know their fate in many cases. 17. My grandfather's brother, Nissen Levinsohn, had a farm at Kimale (Kimales krogas majas), on which both families were photographed here around 1924. Four members of this family stayed and were killed in 1941. A grandson, Max, whose father was not Jewish was rescued from being killed and passed away about 15 years ago; he was the only source of information on the others' fate. 18. Information on other relatives and friends is incomplete, but may become known via a current project to document the fate of the Jews who remained in Latvia at the time of the Holocaust. The collection of paths is quite diverse. In this picture, for instance, taken in the mid-1920s, two went to South Africa, two to Israel, two were killed and the fate of the seventh is unknown. 19. The synagogue building that we are here to discuss is a mute symbol of what was once a thriving community. Many members of that community went on to live long and productive lives elsewhere, but for others Kuldiga was their lifelong home. The few remaining tombstones in the cemetery on Liepajas iela represent a much larger number of former residents, but those who were killed in 1941 have not even been fully identified, not to mention being commemorated as individuals. The synagogue restoration project provides an opportunity to recognize them especially among the larger community for whom the building was an important focus and symbol in their lives. |