Origins of the Courlander Jews and

Life of the Jews in Goldingen/Kuldiga

by Martha Levinson Lev-Zion, PhD

|

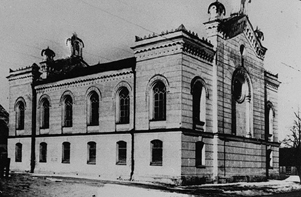

The first evidence we have of Jews in Courland comes from graves dating from the 14th century. However, it is possible that these Jews died while passing through Courland since, with rare exceptions, there was a prohibition against Jews living in the region. The first incontrovertible written evidence of the Jews in the area dates from a journal written in 1535. Where did the Jews come from and why? I would like to suggest that one might form a firm hypothesis about the origins of the Courlander Jews by taking into account the events in central Europe at that time. The 14th century in Europe was a time of terrible persecution for the Jews. You might recall that during the time of the Black Death, in the mid-1300s, not only did Jews contract and die of the disease, but they were also accused of having caused the plague and were subsequently tortured, pilloried and burned to death. They were accused of poisoning wells and were massacred. Because they were a literate people, they were looked upon with suspicion and many were considered witches and condemned to burn at the stake. At various other times, they were merely driven out of different areas, expulsed from certain territories and forced to wander once more. Where were these banished Jews to go? It is an interesting phenomenon that as one state expelled its Jews, another was there on the sidelines encouraging them to come. In general, the movement of migration during the 14th to the 16th centuries was in an easterly direction. The Iberian Jews spread out across Europe. They settled in France, parts of the Holy Roman Empire, in Amsterdam, in Turkey and beyond. Almost always, the local burghers, or merchants, were against Jews settling in their area because they did not want the commercial competition. On the other hand, the landed gentry, petty landholders and local potentates were interested in encouraging the Jews to settle in their jurisdictions in order to promote trade, bleed them to the maximum in order to fill their own treasuries, and to use them as industrial developpers, and negociants for the importation and exportation of goods. The greatest opposition to the settlement of Jews in any area came from the various guilds. The local rulers charged Jews for their movements in and out of the territory; charged them and their families a head tax for every Jew settled in the area; extorted large sums for a Schutzbrief, or a letter of protection; and charged them taxes on their goods. In short, the Jews had to pay for just about every aspect of their lives except for breathing. Travelling Jewish merchants covered great distances and served as a sort of telegraph system spreading news among the various communities, both news of the Jews and news of other communities. They related how different principalities treated the Jews, where it was easier to eke out a living, what products were wanted where, what the needs were of various Jewish and non-Jewish communities, the general state of affairs, and so forth. In 1550, the Jews had nearly been eliminated from the economic life of west and central Europe. Central European Jews were being chased from their homes in the Holy Roman Empire. Coincidentally, Poland-Lithuania was in the process of stabilizing its regime and had an interest in expanding trade and settling the nether regions of the territory. Although the Catholic Church and the burghers continually pressed the Grand Dukes to disallow the Jews privileges and rights, the Dukes were generally religiously liberal and saw in the Jews the advantages of a loyal and knowledgeable citizenry. Even when they were forced to give in to the pressures of the Burghers and the Catholic Church, the Dukes ignored the resulting charters that were agreed upon and encouraged the Jews to settle in their area. They appointed the Jews to important economic positions such as brokers for the Court, tax collectors, negociants, and so forth. So just as the Jews were being forced out of western and central Europe, they were being encouraged to settle in eastern Europe. These same Jews were later to make up the bulk of the permanent Jewish settlers in Courland. Because of the primitive state of the economy of Poland-Lithuania, the Jews were able to enter into areas where in the Holy Roman Empire, they had previously either been severely limited or excluded entirely. The vast expanses of Poland-Lithuania, just like the Ottoman Empire, were grossly underpopulated. The rulers welcomed the Jews who were needed for their advanced economic know-how, their skills and their wealth, to help populate the vastness of their kingdoms. The Jews developed commerce on a grand scale and became experts in managing the exports of grain and timber. There were no powerful guilds in Poland-Lithuania, which thus allowed the Jews to become artisans and craftsmen. In the nether territories, they were even given land and were able to till the soil, market the produce, manage large estates and develop their skills in animal husbandry. Jews were also given brewing and distilling rights. During the reign of the German Knights, the general prohibition of Jews settling in Courland also held for Goldingen. Poland-Lithuania acquired the Courland area after the defeat of the Teutonic Knights in 1561, and Courland became a sort of semi-independent Duchy, under the nominal protection of Poland-Lithuania. In point of fact, the official prohibition of Jews in Courland did not hold in Goldingen and other places. By the end of the 17th century, Jews from Poland and Lithuania were already found in the areas surrounding Goldingen. They developped trade activities in their areas which soon spread to the city itself. The German burghers rabidly opposed their presence and continuously fought against against any law that would regulate the Jews’ legal standing. Finally, with the regulating of the legal status of all the Jews of Courland in 1799, the Jews of Goldingen also received citizen’s priviledges in the city. The most famous Duke of Courland was Jacob Kettler also known as Duke James. He ruled the Duchy from 1642 to 1684. During his reign, conditions for the Jews not only improved, but he welcomed successful Jewish merchants into the Duchy. Jacob was a great believer in mercantilism and travelled the world to learn more about how the great powers prospered. He was particularly impressed with the Netherlands, whose liberal policies allowed Jews to manage huge influential shipping routes and colonial trade as well as become industrialists and international bankers. When Duke James went to visit his cousin, the Great Elector Frederick William Hohenzollern of Bandenburg-Prussia, his cousin informed him that he had given asylum to Jews exiled or fleeing from neighbouring areas because of their commercial abilities and economic advantages. When the Prussian merchants complained about the competition, Frederick William told them that he believed that the Jews were useful to the land. Not only that, but Frederick William invited Jewish merchants to settle in the port of Memel, which he hoped to use as a counterweight to Königsberg, whose townsmen and nobles spearheaded the opposition to the Great Elector's mercantile plans to introduce Jews into the area. Noting his cousin's successful mercantile policies, as well as those of other countries, Jacob introduced industries such as sawmills, manufacturing enterprises for glass, soap, weapons, gunpowder, paper and textile mills. He even went in for armed merchant ship building in such a big way that it was said that there were more ships in Courland than in neighbouring Denmark and Sweden! (1) It was not just in port cities such as Libau and Windau that shipyards were built, but in Goldingen as well. Even England and Venice ordered ships from Courland! The Duke's ships plied the colonial trade and brought in goods such as sugar, coffee, spices and tobacco that were then sold in Courland, Livonia and in the neighbouring countries. In fact, the Duke had his own colony when in 1645 he purchased the West Indian island of Tobago. He then collaborated with a group of Dutch Carribean Sephardi families to develop sugar and tobacco production on the island. With the end of Duke Jacob's modern reign, the burghers constantly pressured the new authorities to expel the Jews, which was finally agreed upon in 1692. But only in 1714 did the reigning Duke Ferdinand Kettler II issue a decree giving the Jews 6 weeks to leave the Duchy. But it didn't happen. The Jews were able to pay an annual sum for a Schutzbrief that would enable them to stay. But this is what characterised the history of the Jews in Courland right up to their expulsion in WorldWar I: The merchants constantly decried them to the authorities and clamoured for their banishment; the nobles, who were interested in the economic advantages that the Jews could arrange for them, opposed the burghers. When Russia took over the area, their long history of anti-Semitism continued as they made decrees against continued rights of Jews and Jewish settlement, which were rarely carried out because the estate owners protected them. Proof of this is that we read the same law being enacted and re-enacted time and time again, which certainly would not have been necessary, should it have been enforced the first time around. In Goldingen in 1797, there were 26 Jewish males enumerated, out of a general population of of 711 Germans. Already by 1801, the Jews had established a chevra kaddisha – a burial society – and had begun to keep a community register (pinkas). One could say that the official Jewish community of Goldingen formally dates from that year. By the first quarter of the 19th century, all of the Jewish community institutions were well in place and there were regular community meetings, discussions, charities and registers (pinkasim). Alas, these pinkasim were burned up and lost when the city caught fire in 1859. The first rabbi was installed in 1826, but had great difficulties because the appointment had to be approved by the Russian government, which did not give its blessing. By 1835, the Jews numbered 2,330 or 57% of Goldingen’s population which stood at a total of 4,053. As the 19th century wore on, more and more Jews and Latvians came to settle in Goldingen, which thus slowly lost its uniquely German character. Between 1830 to 1880, the number of Jewish merchants in Goldingen increased by 63, while during that same time the number of Russian and German merchants only increased by four. Those who could afford it sent their children to the famous German Gymnasium in town, which because of its high level of education, attracted students from all over the Baltics. In 1888, some Jewish industrialists set up a Talmud Torah for children of the poor so that these children could also receive an education. However, at the beginning, their parents were required to pay something towards their tuition which prevented the children from attending. In the end, the Talmud Torah was totally subsidized by the Jewish community and the children learned for free both secular and religious subjects. There was also a Russian school in Goldingen/Kuldiga, but because of rampid antisemitism within the school, Jewish children did not to attend. In 1902, an occupational school opened which welcomed all children. In 1915, after the outbreak of World War I, the Jews of Kuldiga were uprooted, torn out of the city with 48 hours notice and expelled into the interior of Russia. This caused great economic hardship for the remaining citizens of the city due to severe shortages of basic goods and the sudden spiking of prices. In the end, many of the non-Jewish citizens also left Kuldiga, but, they, of their own free will. After the war, in the 1920’s, only about a third of the Jews returned, reducing their numbers to only about 12% of the total population of Kuldiga. Their economic situation was disastrous. They had had to leave everything behind when they were uprooted and when they returned, nothing remained to them of what they had left. Everything had been taken. Only 30% of those Jews who returned had a source of livelihood. The remaining 70% had nothing, not even a roof over their heads. Thanks to help from the Joint Distribution Committee, the community began to rehabilitate itself. They built back up their community institutions and founded a new Jewish cemetery in the town. They also founded a new Jewish German language school, even though most of the Jewish students went to the non-Jewish German language school because of its high academic level. They once again began to take an important economic role in the city. By 1935, they had worked their way back up the economic ladder and from nothing, they now owned 80% of all imports and electrical equipment shops; 77% of leather goods and shoes stores; 64% of textile materials; 57% of books and paper goods and so forth.(2) When the Soviets took over, between 1940-1941, they slowly destroyed Jewish communal life in Kuldiga. With the outbreak of the war between the Soviets and Germans in June, 1941, about 1/10th of the Kuldiga Jews escaped into the interior of the Soviet Union. The majority of the Jewish community remained in place. The first of July, 1941, the Germans conquered Kuldiga and a group of Latvians, including a group of former Aizsargi began to beat up and kill Jews. The first Jewish victims fell to them, their fellow citizens. The remaining Jews were obliged to do hard labour. They were forced from their homes and locked into the Synagogue. After a short time, a group of men was taken out and was murdered in a pit that they had been forced to dig in the neighbouring forest. After that, the rest of the Kuldiga Jews were murdered in the Padura Forest, a few kilometers outside the town, and in other places. The murderers were classes of marksmen made up of Latvian policemen. The rich Jews were forced to run from the pit with the dead bodies back again to the city, so that they would reveal all the places where they were supposed to have buried their valuables, and in the end, they too were murdered. By the beginning of 1942, there was no longer a Jewish community in Kuldiga. An exceedingly small number of Jews found refuge from the slaughter with farmers from the area. Everything the Jews owned was split up among the Latvian murderers and the Torahs were put into the city archive. After the war, a number of families who had fled to the Russian interior returned. They recorded testimonies from the Kuldigers on what had happened to the Jews of Kuldiga. They reburied their murdered brethren in a common Jewish grave in the cemetery. They had a minyan in one of their private homes and the Torahs were returned to them. But not the Synagogue, which had been turned into a cinema. With time, the veteran Kuldiger Jews began to leave, some going to Israel. Into Kuldiga came other Jews from different places in the Soviet Union. Before they left, the veteran Kuldigers put up a tombstone in the cemetery and inscribed upon it, “Brothers’ Grave” in Latvian. After the old Kuldiger Jews left, the cemetery became neglected and in the end, the government eliminated it. And in this way came the ignominious end of the Jewish community of Kuldiga. (1) Levinson, Isaac: The Untold Story. Kaylor Publishing House. Johannesburg., 1958. P. 76 (2) Levin, Dov: Pinkas Hakehillot Latvia v’Estonia, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1988. p. 220 (in Hebrew) |