The Aporia of Forgetting

by Aida Miron

|

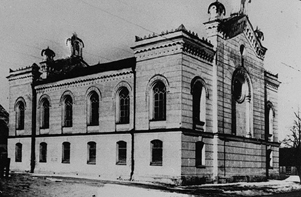

>> Die Aporie des Vergessens “No one bears witness for the witness. In the rivers north of the future I cast out the net that you, wavering, weigh down with shadows written by stones. Deep in the time-crevasse, by the honeycomb-ice there waits, as a breath-crystal, your unimpeachable testimony. “ Celan, Breath-Turn , Atemwende When we speak of “reconstructed memory,” in Latvia, we must analyze the discourse of forgiveness and forgetting. Being faced not only with the aporia of remembrance, but of place and a collective forgiveness, the moment we open this space of assembly/prayer -the synagogue, to discussion, we enter the aporia of the impossible and the “immemorial.”(1) It is through questions and anxieties that we will begin to comprehend the necessity to address the silences of history, even through the incapacity of language, or the impossibility of a finished project, and address “that,”(2) which invokes the impossibility of speech. It is through dialogue that we will be able to think through the pressing issue of the synagogue and Jewish memory, and think of possibilities. It is within this address of the synagogue and discussions of its renovation/reconstruction that we begin to distinguish between silences and the question of bearing witness and responsibility. For it is one thing to respect the silence or unwillingness of the witness to speak, or the inclination of certain writing/spaces “towards silence,”(3) and another to confuse the silencing of the witness, or the silent witnessing of their extermination. Discourse cannot evade responsibility because of its incapacity to address the “unspeakable.” In a similar way, the project of reconstruction cannot be evaded, because evasion runs the risk of a double violence and amnesia. The emphasis here is not an architectural reconstruction, but a projection of the possibility of reconstruction. But what does such a project entail? Do we run the risk of misappropriation when we invoke transformations and substitutions, and think of the memorial, monument, or new programs: museum, library, etc? We do not approach the synagogue as a building or symbol, but as that which includes within its presence the absence of its community and the memory of the Shoah. We have here the aporia of place, of that which is beyond its presence, and speaks of the absent, of the witness, of memory, and silence. How then to address the synagogue in contemporary times in Latvia? How to open this discourse to the “community,” open up the discourse of responsibility? How to address this place of prayer and thought in the case where there is no longer a community to appropriate it. Or is there the possibility of a return, of the return of the witness, or the return to the witness? The return of a community, of its descendants, of the exiled, a return to the memory, or to the place. In the instances when there are no longer survivors the synagogue stands as testimony. But what happens when this testimony is no longer present but in its absence more pressing? (4) (As in the case of the testimony of the one who was never able to testify, the disguised mass grave, the burned/destroyed synagogue, the destroyed community, the removed trace of the extermination, in their absence affect the present.) (4a). Most synagogues in the Baltic region were destroyed, how then do we approach the unaccountable sites of former synagogues, cemeteries and burial places? How do we begin to trace them? Is the memorial, or monument the proper way of address, when absence is the very thing that escapes representation? It is in this representation where traces run the risk of being if not effaced, forgotten. Lyotard argues that in the politics of forgetting, (itself apolitical), carried on after “Auschwitz”….”there are at least two kinds of this politics: the first proceeds by effacement, the other by representation… Whenever one represents, one inscribes in memory, and this might seem like a good defense against forgetting. It is… just the opposite. Only that which has been inscribed can, in the current sense of the term, be forgotten, because it could be effaced (5) … it is to be feared that through representation, it [the Shoah] turns into an “ordinary” repression (Lyotard 26).” We must not confuse this danger of inscription with writing, or think that representation could be evaded, but we must proceed with care and highlight the extreme danger in some cases of the approach of the memorial. This being the case, where the memorial or “project” tries to totalize the fragment or trace, and through representation of memory forget what is in question. How is this responsibility related to the asking of forgiveness, or to forgetting? How to live with the presence of a past, when it recalls “that” which calls for an un-assumable responsibility and it is not past? When asked if one should forgive, Vladimir Jankélévitch answers that “we must not forgive… nor forget.” For Derrida, the question of collective pardon refers especially to places, and moments: “who asks whom for forgiveness at what moment? …. Does one forgive someone or something, whom or what?” Derrida rereading Jankélévitch asks if there is such a thing as the possibility of true forgiveness, measured against “the impossible,” Jankélévitch answers: “that forgiveness died in the death camps… that the history of forgiveness…this history has come to an end.”(6) Being well beyond the human scale, forgiveness asks the impossible, it is the aporia of forgiving, for it must forgive the unforgivable: “the singularity of the Shoah reaches the dimensions of the inexpiable (Derrida II).” The relation between victim/perpetrator is well beyond the realm of ethics. Agamben addresses a similar question of responsibility in relation to ethics. Placing forgiveness and ethics outside the realm of the juridical, Agamben analyses the “grey zone” of responsibility between perpetrator and victim, where the juridical is closely related to guilt, and ethics is well beyond the category of judgment and cannot assume “a responsibility infinitely greater than what we could ever assume (Agamben 11).” After Auschwitz, ethics finds itself confronted with a “grey zone”…… a zone of irresponsibility between the “human and inhuman.” Here testimony is the abyss between thought and the unthinkable: “Maybe all words, all writing is born, in this sense like testimony, and because of this, that which it testifies could no longer be language, no longer be writing, and could only be the non-testimony. This is the sound which reaches us from the abyss, the non-language which speaks alone, with the correspondence of language and from which it is born (Agamben 20).” It is along the same line of this thought of the abyss that Lyotard encounters Adorno’s thought, which “remaining in the abyss, confronted with its own disaster, is struggling not to continue along its representational line but approach what has not been able to think and what it cannot think… philosophy as architecture is ruined, but a writing of the ruins, micrologies, graffiti can still be done (Lyotard 43).” If there is still the possibility of a thinking/writing after the disaster, one of fragmentation and ruins,(7) how do we think through an architecture of ruin? From Kafka to Celan to Benjamin, we find this writing “that preserves the forgotten.” We find a writing which has been transformed and in its fragmentation comes closest to bearing witness. It is within these fragmentary writing, and turning in language (or breach) that we could begin to confront the traces in question. How does this thought of the abyss, this caesura in history, this breaking of language relate to the traces of Jewish memory in question? For here we are also dealing with fragments and ruins, and it is essential to approach the architectural project in question as a preservation of the “forgotten.” For in its current state of ruin and within the property of the abyss, the synagogue as what remains of something destroyed: a community, language, place and memory, addresses the very forgotten. If in language and thought we find a movement towards an outside of language, towards an other of writing, beyond the limitations of what could be thought and spoken of, how do we address this absence/breach in architectural terms? Is there a possibility of rebuilding from debris? “Whichever stone you lift you lay bare those who need the protection of stones… whichever word you speak you owe to destruction (Celan).” What then does the synagogue in ruin/disuse represent and to whom? Is it possible to “reconstruct” this space without exposing “those who need the protection of stones?” We must begin by respecting this very place, and retracing the histories affiliated with each synagogue. Is it possible to return, to reconstruct, and recuperate when appropriation already implies an erasure of the trace? What does it mean to preserve/reconstruct in the current urban and civil context of Kuldiga? We could begin by asking what is proper, in terms of appropriation and property. What is the appropriate program for this space? To speak of a change of program, memorial, and transformation runs the risk of misappropriation, but to confront the current state of neglect with another silence, runs the risk of effacement and forgetting. We must walk through these ruins carefully, and listen attentively to the silence that emanates from them, for “caesura makes meaning emerge (Derrida I, 71).” Fragmentation unfolds sites of multiple discontinuities, leaving traces and silences to interpret. How do we move through these traces towards the possibility of a reconstruction of place? How do we move from trace to place? What is the future of the synagogue after the Shoah? We must respond to this pressing question, even though we are entering the aporia of the unspeakable, outside of language and representation, in the realm between the possible and impossible. Notes: 1. Lyotard refers to the “paradox of the immemorial” found in Deleuze and Freud, something that comes close the past in A la Recherché du temps Perdu “the sort of past that interest us here, a past located this side of the forgotten, much closer to the present moment than any past, at the same time that is incapable of being solicited b voluntary and conscious memory-a past…that is not past but always there (Lyotard 12).” 2. “What died in him at Chelmo?” “Everything died. But he’s only human, and he want to live. So he must forget. He thanks God for what remains, and that He can forget. And let’s not talk about that.” -Michael Peldchlbnik in Lanzmann’s Shoah 3. “Poetry today shows a strong inclination towards silence…” Paul Celan 4. “A past that is not past, that does not haunt the present, in the sense that its absence is felt, would signal itself even in the present as a specter, an absence, which does not inhabit it in the name of the full reality, which is not an object of memory like something that might have been forgotten and must be remembered…it is thus not even there as a “blank space,” as absence…but it is there nevertheless…(Lyotard 11).” 4a. “The Jews murdered en masse are, absent, more present than the present (Lyotard 39). ” 5. Lyotard explains the Nazy politics as one of absolute forgetting,“ carried on through effacement and representation: “Obviously a politics of extermination exceeds politics (25)“ but one must not confuse representations for .....“One must certainly inscribe in words, in images. One cannot escape the necessity of representing. It would be sin itself to believe one safe and sound. But it is one thing to do it in view of saving memory , and quite another to the to preserve the remainder, the unforgettable forgotten, in writing (Lyotard 26).” 6. Derrida is referring to the work on Jankélévitch’s work of 1971 on the question of Le Pardon, and forgiveness. (Derrida “Violence and Forgiveness”). 7. In Edmund Jabes and the Question of the Book, Derrida speaks of the voice of the poet: “writing is itself written, but also ruined, made into an abyss, in its own representation…(65), later on he explains that: “The fragment is neither a determined style nor a failure, but the form of that which is written….the caesura does no simply finish and fix meaning…the caesura makes meaning emerge (Derrida, Writing and Difference 65,71).” 8. Celan, Paul, Welchen der Steine Du Hebst / Whichever Stone You Lift, from (Von Schwelle zu Schwelle/Threshold to Threshold). 1955. Bibliography Agamben, Giorgio (1999). LO QUE QUEDA DE AUSCHWITZ. El archivo y el testigo, HOMO SACER III, PRE-TEXTOS. [Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive.] Celan, Paul, Poemas. Traducción de Pable Oyarzun. Escuela de Filosofía, Universidad ARCIS. Derrida (I), Jacques, Seminar: “Violence and Forgiveness,” New York University, Oct 2, 2001. Derrida (II), Jacques, Writing and Difference, The University of Chicago press, 1978. Lyotard, Jean-Francois. Heidegger and the ‘jews’. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1990 |